The Excruciating Choice

Governments face an “excruciating choice” between “flattening the (coronavirus) curve” by imposing quarantines and lockdowns and the huge, unprecedented economic impact on the world economy that is already in recession. The Health and Human Services Department of the US Federal Government is planning for the possibility of an 18-month medical and economic crisis (Bublé, March 18, 2020).

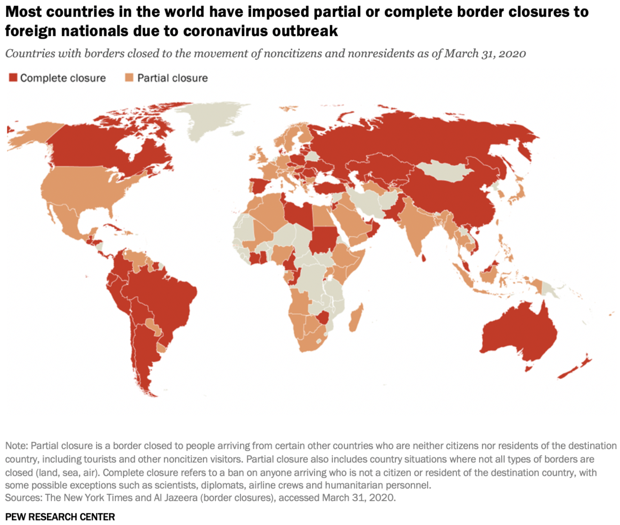

While pandemics have occurred in the past, the global scale of overnment response verges on the unimaginable. According to a Pew Research Center report, as of March 31, 2020, 93 percent of the world’s population lived in countries with at least some travel restrictions (Connor, April 1 2020). This means that much of the world economy is either hampered, delayed, or shut down entirely (Fernandes, March 22, 2020). In the worst scenario, if prolonged, this could lead to not just a global recession, but something worse.

Source: Connor, P. (April 1, 2020). More than nine-in-ten people worldwide live in countries with travel restrictions amid COVID-19. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/04/01/more-than-nine-in-ten-people-worldwide-live-in-countries-with-travel-restrictions-amid-covid-19/

Are the “Copycat” Government Responses Worldwide Appropriate or Excessive?

What is driving this “copycat” behavior on the part of all nations? Is it an excessive reaction? What will be the consequence– returning to normalcy faster or plunging the world into a prolonged recession? Governments are closing businesses and imposing quarantines or travel restrictions with the idea of slowing the spread of the coronavirus. But will slowing its spread also prolong the economic anguish? Will it also reduce the number of persons eventually infected?

For readers interested in the above questions, this piece is intended as another update to my earlier post (Contractor, March 20, 2020) with additional references from medical experts and economists. I also indicate below why there are no definitive answers yet (Knowledge@Wharton, March 24, 2020) and why the estimates in the scholarly epidemiological references below should be read with circumspection.

What Does “Flattening the Curve” Mean?

The expression “flattening the curve” is already a popular cliché. What a government means by this – and it is an admission of unpreparedness – is that, unchecked, infections would grow at an exponential rate so as to exceed the capacity of hospitals to cope with the numbers of patients. For a graph and additional details, see my earlier post (Contractor, F., March 20, 2020).

By forcing quarantines and social distancing, governments hope that the growth of the infections will slow to a rate that remains below the maximum capacity of hospital beds, equipment such as ventilators, and doctors and nurses available in their region or country. If not, the medical establishment will be overwhelmed. This is already happening in Italy, Spain, New Delhi, and New York (as of April 2, 2020). For a while, it happened in Wuhan and Hubei Province, whereupon the Chinese government introduced a severe lockdown on January 23, 2020.

But What About the Severe Impact of Shutting Down Some or Much of the World Economy?

While restrictions are being gradually eased in Hubei, scant signs of an economic recovery there are evident as yet. As the diagram in my previous post (Contractor, March 20, 2020) schematically illustrates, “flattening the curve” also means prolonging the economic dislocation, precipitating mass unemployment (perhaps more than 60 million have been laid off worldwide in just the last two weeks), bankruptcies, and the mental and physical health effects of an extended downturn in the medium to long term.

Are Governments Acting Appropriately or Over-Reacting?

Candidly, we have no definitive answers as yet. While economic papers (e.g., Bonaparte, 2020; Fernandes, 2020; Gourinchas, 2020) try to model the effects, all modeling is based on assumptions, and the current situation poses way too many unknowns or gaps in data (Stock, 2020). For example:

- Using the 1918 pandemic experience as an example is hardly analogous.

- The coronavirus is different, and its virulence, mutation rate, propensity to linger in warmer weather, persistence, and return are unknowns at present.

- The world of 2020 is vastly more globalized and interdependent than ever before.

- Supply chains in world trade are orders-of-magnitude more complex. Subcomponents, parts, and components cross country borders multiple times before being finally assembled, all under the aegis of multinational companies (MNCs). For example, UNCTAD (2013) estimated that in 80 percent of all world trade (amounting to around $US 20 trillion in 2019), a MNC was either an exporter or an importer, on one side of the trade deal, or participated as an orchestrator of a global value chain. Equally remarkably, the same MNC was both the importer and the exporter (i.e., simultaneously on both ends of the shipment) in approximately 40 percent of world trade, and Lanz and Miroudot (2011) found that in 2009, 58 percent of US goods imported from OECD countries were intra-firm.

- With 93 percent of the world’s population living in countries with restrictions imposed because of the virus, the scale of this slowdown or shutdown is utterly unprecedented.

- Companies, municipalities, and individuals are more vulnerable because, tempted by historically low interest rates post-2008, many borrowed recklessly, and their leverage or debt:equity ratios are dangerously near record highs (Srivastava, 2019).

- Epidemiological modeling (e.g., Flaxman, Mishra & Gandy, 2020, or Correia, Luck & Verner, 2020) is also prone to greater uncertainties because the behavior of the current virus is not exactly mapped yet.

- The world population is at an all-time high of 7.7 billion.

- Crowding or urbanization now includes over 60 percent of humanity, which is at a record level.

- Average temperatures worldwide are higher, which may decrease the incidence of certain viruses, but increase disease transmission in general (World Health Organization, 2020; Luber, et al., 2014).

- In 2019, 4.7 billion airline tickets were sold, and cross-border tourist visits numbered more than 1.5 billion.

- All of the above elements point to increased vulnerabilities of the global economy, but on the positive side,2 billion − or almost half the planet − had access to the internet, were better informed and more educated, and were more likely to comply with government orders or recommendations.

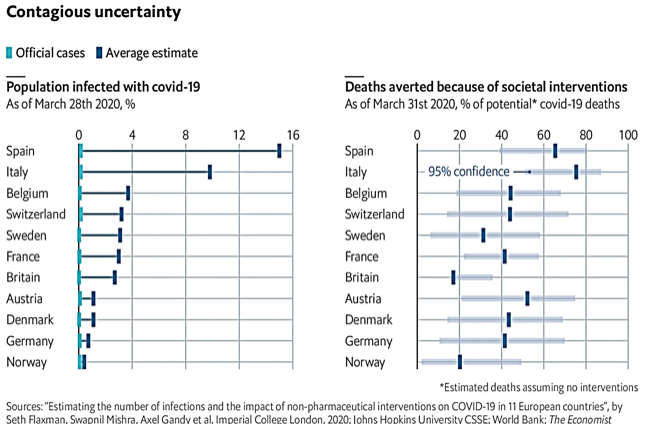

The degree of uncertainty in modeling is illustrated in Flaxman, Mishra & Gandy (2020) and in The Economist (April 1, 2020), where the “95% confidence” interval is itself as broad as 50 percent for more than half of the countries studied.

Source: The Economist, April 1, 2020. https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2020/04/01/covid-19-may-be-far-more-prevalent-than-previously-thought

The degree of uncertainty even among medical experts is demonstrated by the estimate in the above chart, For instance, for Germany the mean “% of potential covid-19 deaths” averted is estimated at 41 percent, but the 95 percent confidence interval ranges widely from 12to 70. For Belgium, the mean is 44, but the confidence interval ranges from 18to67. This is true for most of the countries studied.

How History Will Judge This Period

For interested readers, my earlier post (Contractor, March 20, 2020) describes the trade-offs and the excruciating dilemma for governments and describes the logic behind “flattening the curve.” In short-term health effects, there is no question that shutdowns and quarantines are the right thing to do, according to Gourinchas (2020), Correia, Luck & Verner (2020), and this graph in The Economist. But “flattening the curve” also means prolonging the world recession to an unknown extent, which itself may have grave long-term economic and health consequences. Only history will judge whether the trade-off was appropriate.

In Conclusion: Will Globalization Retreat?

For International Business, 2020 will be remembered as an inflexion point that adjusted or restructured MNC operations, global value-chains, the role of governments in regulating foreign direct investment (FDI), protectionism, the change in the behavior of managers to take risks (i.e., the uncertainty-avoidance behaviors of managers), propensity to form cross-border alliances, country-of-origin influences on consumer purchases (Samiee, Shimp & Sharma, 2005), and myriad other global business decisions – thus formulating a new agenda for the future of globalization.

Will globalization retreat? Probably not. Although there likely will be more national controls, local value-added mandates, and nationalism, the underlying logic of global business will remain valid. What is the underlying logic? Specialization and concentration – the idea that certain types of products or services, or certain functions, are more efficient (i.e., cheaper) when concentrated in certain countries or cities, from where they can be distributed locally and internationally. The opposite model – each nation trying to make everything domestically – is not only far more expensive, but also simply not feasible for most of the smaller nations on the planet.

Politics and global economics will remain in uneasy tension. The number of countries on the surface of our planet (193 at last count in 2020) is three-and-a-half times larger than the number of nations that existed in 1960. But that did not stop the phenomenal expansion of trade and FDI over the past 60 years. Nationalism and concocted patriotism course through Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp. But each message recipient also knows – subconsciously – that the smartphone they are holding in their hands would cost three to ten times more if produced entirely locally.

As a consumer, which is more important to you? The satisfaction of a smug national or local identity with most products and services costing much more than they do today? Or the slight psychological discomfort that internationalization causes for your identity and self-worth* while you enjoy lower prices and consequently a higher standard of living in material terms? I leave that as an open question for the future (and future blog posts).

*See my previous posts: What Is Globalization? How to Measure It and Why Many Oppose It (Part 1) and Global Leadership in an Era of Growing Nationalism, Protectionism, and Antiglobalization (Part 2).

REFERENCES

Bonaparte, Y. (March 5, 2020). Pricing the Economic Risk of Coronavirus: A Delay in Consumption or a Recession? Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3549597 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3549597

Bublé, C. (March 18, 2020). Coronavirus Roundup: Federal response could last 18 months. Government Executive. https://www.govexec.com/workforce/2020/03/coronavirus-roundup-news-about-outbreak-matters-feds/163882/

Connor, P. (April 1, 2020). More than nine-in-ten people worldwide live in countries with travel restrictions amid COVID-19. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/04/01/more-than-nine-in-ten-people-worldwide-live-in-countries-with-travel-restrictions-amid-covid-19/

Contractor, F. (March 20, 2020). The excruciating choice: “Flattening the curve” and prolonging the global recession. GlobalBusiness.Blog https://globalbusiness.blog/2020/03/20/the-excruciating-choice-flattening-the-curve-and-prolonging-the-global-recession/ (updated March 23, 2020: https://globalbusiness.blog/2020/03/23/quick-update-the-excruciating-choice-flattening-the-curve-and-prolonging-the-global-recession/).

Correia, S., Luck, S. & Verner, E. (March 30, 2020). Pandemics Depress the Economy, Public Health Interventions Do Not: Evidence from the 1918 Flu. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3561560 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3561560

Fernandes, N. (March 22, 2020). Economic Effects of Coronavirus Outbreak (COVID-19) on the World Economy. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3557504 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3557504 or https://mediaroom.iese.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Fernandes-Nuno_20200322-Global-Recession-is-inevitable.pdf

Flaxman, S., Mishra, S. Gandy, A. et al. (March 30, 2020). Estimating the number of infections and the impact of nonpharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries, Working Paper, Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team DOI: https://doi.org/10.25561/77731

Gourinchas, P-O. (March 18, 2020). Flattening the pandemic and recession curves. Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever It Takes. Available at: VOX. https://voxeu.org/content/mitigating-covid-economic-crisis-act-fast-and-do-whatever-it-takes

Pandemic Panic: Can governments protect jobs and markets? Interview with Mauro Guillen (March 24, 2020). Available at:

https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/layoffs-loom-governments-respond-pandemic-panic/

Lanz, R. & Miroudot, S. (2011). Intra-Firm Trade. Patterns, Determinants and Policy Implications. OECD Working Paper No. 114. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/241764228_Intra-Firm_Trade_Patterns_Determinants_and_Policy_Implications

Luber, G., K. Knowlton, J. Balbus, H. Frumkin, M. Hayden, J. Hess, M. McGeehin, N. Sheats, L. Backer, C. B. Beard, K. L. Ebi, E. Maibach, R. S. Ostfeld, C. Wiedinmyer, E. Zielinski-Gutiérrez, & L. Ziska, 2014: Ch. 9: Human Health. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, Eds., U.S. Global Change Research Program, 220-256. doi:10.7930/J0PN93H5 https://data.globalchange.gov/report/nca3/chapter/human-health

Samiee, S., Shimp, T. A. & Sharma, S. (2005). Brand origin recognition accuracy: Its antecedents and consumers’ cognitive limitations. Journal of international Business studies, 36(4), 379−397. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5223148_Brand_origin_recognition_accuracy_Its_antecedents_and_consumers’_cognitive_limitations

Srivastava, S. (November 15, 2019). Global debt surged to a record $250 trillion in the first half of 2019, led by the US and China. CNBC.com. https://www.cnbc.com/2019/11/15/global-debt-surged-to-a-record-250-trillion-in-the-first-half-of-2019-led-by-the-us-and-china.html

Stock, J. H. (March 26, 2020). Data gaps and the policy response to the novel coronavirus (No. w26902). National Bureau of Economic Research.

The Economist (April 1, 2020). Daily Chart: Covid-19 may be far more prevalent than previously thought.

The Economist (March 31, 2020). Daily Chart: Lessons from the Spanish flu: social distancing can be good for the economy.

UNCTAD (2013). World Investment Report: Global Value Chains, Investment and Trade for Development. Geneva: United Nations. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2013_en.pdf

World Health Organization (accessed April 2, 2020). Climate Change and Human Health. https://www.who.int/globalchange/climate/summary/en/index5.html.

I really loved reading your blog. It was very well authored and easy to understand. Unlike other blogs I have read which are really not that good.Thanks alot!

kamagra 100mg prix: kamagra gel – Kamagra pharmacie en ligne

cialis generique cialis generique cialis sans ordonnance tadalmed.com

Pharmacie sans ordonnance pharmacie en ligne pas cher or pharmacie en ligne france pas cher

http://www.constructionnews.co.nz/Redirect.aspx?destination=http://pharmafst.com/ pharmacie en ligne livraison europe

pharmacie en ligne livraison europe Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe and pharmacie en ligne france pas cher pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance

http://kamagraprix.com/# kamagra livraison 24h

acheter kamagra site fiable kamagra 100mg prix or kamagra pas cher

https://forum.keenswh.com/proxy.php?link=http://kamagraprix.shop kamagra pas cher

achat kamagra Achetez vos kamagra medicaments and kamagra en ligne kamagra 100mg prix

Achetez vos kamagra medicaments Kamagra pharmacie en ligne Kamagra Oral Jelly pas cher

Cialis sans ordonnance pas cher: Cialis sans ordonnance pas cher – Cialis generique prix tadalmed.shop

https://tadalmed.com/# Cialis sans ordonnance 24h

Pharmacie en ligne Cialis sans ordonnance cialis generique Cialis sans ordonnance pas cher tadalmed.com

pharmacie en ligne: pharmacie en ligne livraison europe – Pharmacie sans ordonnance pharmafst.com

http://pharmafst.com/# vente de mГ©dicament en ligne

pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique pharmacie en ligne fiable or pharmacie en ligne france fiable

https://www.ssbonline.biz/speedbump.asp?link=pharmafst.com& pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance

Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale and п»їpharmacie en ligne france pharmacie en ligne livraison europe

kamagra 100mg prix: kamagra oral jelly – Acheter Kamagra site fiable

kamagra oral jelly kamagra livraison 24h achat kamagra

achat kamagra: kamagra pas cher – kamagra oral jelly

https://tadalmed.shop/# Acheter Viagra Cialis sans ordonnance

Acheter Cialis: cialis prix – Tadalafil 20 mg prix sans ordonnance tadalmed.shop

Cialis sans ordonnance 24h Cialis generique prix or cialis generique

https://maps.google.ne/url?q=https://tadalmed.com Cialis sans ordonnance 24h

cialis prix Acheter Cialis 20 mg pas cher and Tadalafil achat en ligne Cialis sans ordonnance 24h

Achetez vos kamagra medicaments achat kamagra or acheter kamagra site fiable

https://www.google.co.kr/url?sa=t&url=https://kamagraprix.shop Acheter Kamagra site fiable

kamagra oral jelly Kamagra Oral Jelly pas cher and kamagra oral jelly Kamagra Commander maintenant

kamagra livraison 24h achat kamagra or kamagra livraison 24h

http://new.0points.com/wp/wp-content/plugins/wp-js-external-link-info/redirect.php?url=https://kamagraprix.com kamagra pas cher

Acheter Kamagra site fiable kamagra pas cher and Achetez vos kamagra medicaments kamagra 100mg prix

kamagra gel: achat kamagra – kamagra oral jelly

https://pharmafst.shop/# vente de mГ©dicament en ligne

pharmacie en ligne fiable: Meilleure pharmacie en ligne – Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable pharmafst.com

cialis sans ordonnance Acheter Viagra Cialis sans ordonnance Tadalafil achat en ligne tadalmed.com

pharmacie en ligne pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale or pharmacie en ligne france livraison internationale

http://www.google.com.fj/url?q=https://pharmafst.com Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable

pharmacie en ligne france pas cher Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe and Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable pharmacie en ligne france fiable

Tadalafil 20 mg prix en pharmacie: Acheter Cialis 20 mg pas cher – Cialis sans ordonnance 24h tadalmed.shop

Pharmacie Internationale en ligne: Medicaments en ligne livres en 24h – pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique pharmafst.com

https://kamagraprix.shop/# kamagra 100mg prix

Tadalafil achat en ligne Tadalafil sans ordonnance en ligne Acheter Cialis tadalmed.com

Acheter Kamagra site fiable achat kamagra or kamagra en ligne

http://cross-a.net/go_out.php?url=https://kamagraprix.shop kamagra livraison 24h

kamagra gel achat kamagra and acheter kamagra site fiable kamagra pas cher

Tadalafil 20 mg prix sans ordonnance: Cialis sans ordonnance 24h – Cialis sans ordonnance 24h tadalmed.shop

Tadalafil sans ordonnance en ligne Achat Cialis en ligne fiable or Acheter Cialis 20 mg pas cher

https://cse.google.sk/url?sa=t&url=https://tadalmed.com Tadalafil sans ordonnance en ligne

Acheter Viagra Cialis sans ordonnance cialis generique and Tadalafil achat en ligne cialis sans ordonnance

Cialis generique prix: Tadalafil 20 mg prix en pharmacie – cialis generique tadalmed.shop

https://kamagraprix.com/# Achetez vos kamagra medicaments

Pharmacie en ligne Cialis sans ordonnance Cialis en ligne Tadalafil 20 mg prix sans ordonnance tadalmed.com

Pharmacie Internationale en ligne: Meilleure pharmacie en ligne – acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance pharmafst.com

achat kamagra: Kamagra Oral Jelly pas cher – Kamagra pharmacie en ligne

Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe or pharmacie en ligne

http://www.startgames.ws/myspace.php?url=http://pharmafst.com/ pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance

pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es п»їpharmacie en ligne france and vente de mГ©dicament en ligne pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique

http://tadalmed.com/# Achat Cialis en ligne fiable

achat kamagra kamagra pas cher or kamagra pas cher

http://www.gorch-brothers.jp/modules/wordpress0/wp-ktai.php?view=redir&url=https://kamagraprix.shop kamagra pas cher

acheter kamagra site fiable acheter kamagra site fiable and kamagra en ligne kamagra en ligne

Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance pharmafst.shop

kamagra 100mg prix: achat kamagra – kamagra livraison 24h

Tadalafil 20 mg prix sans ordonnance Cialis en ligne or Tadalafil 20 mg prix en pharmacie

http://clients1.google.co.za/url?sa=t&url=http://tadalmed.com Cialis sans ordonnance pas cher

Acheter Viagra Cialis sans ordonnance cialis sans ordonnance and Pharmacie en ligne Cialis sans ordonnance Acheter Cialis

Kamagra Oral Jelly pas cher: achat kamagra – kamagra livraison 24h

https://kamagraprix.com/# Kamagra Commander maintenant

pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance pharmacie en ligne livraison europe or п»їpharmacie en ligne france

https://maps.google.cz/url?sa=t&url=https://pharmafst.com vente de mГ©dicament en ligne

Pharmacie sans ordonnance vente de mГ©dicament en ligne and pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es pharmacie en ligne fiable

https://tadalmed.shop/# cialis generique

Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable: Meilleure pharmacie en ligne – trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie pharmafst.com

Achat Cialis en ligne fiable: Acheter Cialis 20 mg pas cher – Cialis sans ordonnance 24h tadalmed.shop

http://tadalmed.com/# Acheter Cialis

pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es pharmacie en ligne livraison europe or pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique

http://reklamagoda.ru/engine/redirect.php?url=http://pharmafst.com pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es

pharmacie en ligne livraison europe Achat mГ©dicament en ligne fiable and Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe pharmacie en ligne fiable

Acheter Cialis 20 mg pas cher: Cialis generique prix – Cialis generique prix tadalmed.shop

Kamagra Oral Jelly pas cher: acheter kamagra site fiable – acheter kamagra site fiable

Tadalafil 20 mg prix sans ordonnance Acheter Cialis or Acheter Cialis

https://www.google.com.np/url?q=https://tadalmed.com Tadalafil sans ordonnance en ligne

Acheter Cialis 20 mg pas cher cialis prix and Cialis sans ordonnance pas cher cialis sans ordonnance

cialis generique: Acheter Cialis 20 mg pas cher – Cialis generique prix tadalmed.shop

Acheter Cialis: Cialis sans ordonnance 24h – cialis generique tadalmed.shop

acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance Meilleure pharmacie en ligne pharmacie en ligne pas cher pharmafst.shop

pharmacie en ligne fiable pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique or trouver un mГ©dicament en pharmacie

https://cse.google.co.th/url?q=https://pharmafst.com acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance

pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance pharmacie en ligne france fiable and Pharmacie sans ordonnance acheter mГ©dicament en ligne sans ordonnance

cialis prix: Cialis sans ordonnance 24h – Pharmacie en ligne Cialis sans ordonnance tadalmed.shop

https://kamagraprix.shop/# achat kamagra

pharmacie en ligne avec ordonnance: Pharmacies en ligne certifiees – Pharmacie Internationale en ligne pharmafst.com

canadian pharmacy 365 Generic drugs from Canada canadapharmacyonline com

northwest canadian pharmacy: adderall canadian pharmacy – canada pharmacy online

ordering drugs from canada: ExpressRxCanada – canadian pharmacy online

http://rxexpressmexico.com/# mexican rx online

canadian online pharmacy reviews Buy medicine from Canada canadian pharmacy store

RxExpressMexico: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

canada ed drugs: Generic drugs from Canada – legitimate canadian pharmacy online

https://rxexpressmexico.shop/# Rx Express Mexico

Medicine From India: Medicine From India – Medicine From India

best canadian pharmacy to buy from: ExpressRxCanada – canadian pharmacy no scripts

online pharmacy india indian pharmacy online shopping medicine courier from India to USA

http://medicinefromindia.com/# MedicineFromIndia

indian pharmacy online shopping: MedicineFromIndia – Medicine From India

Rx Express Mexico: mexico pharmacy order online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

Medicine From India: Medicine From India – Medicine From India

escrow pharmacy canada: pharmacy in canada – safe canadian pharmacy

reliable canadian pharmacy canadianpharmacyworld com or my canadian pharmacy

https://www.google.com.au/url?sa=t&url=https://expressrxcanada.com canadian drugs online

canadian pharmacy checker trusted canadian pharmacy and best canadian online pharmacy reviews canadian pharmacy sarasota

buying prescription drugs in mexico mexican pharmaceuticals online or mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

https://maps.google.be/url?sa=i&source=web&rct=j&url=https://rxexpressmexico.com mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

best online pharmacies in mexico mexican pharmaceuticals online and medication from mexico pharmacy mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

medication from mexico pharmacy mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican online pharmacy

http://rxexpressmexico.com/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

indian pharmacy paypal buy prescription drugs from india or indianpharmacy com

http://4vn.eu/forum/vcheckvirus.php?url=http://medicinefromindia.com india pharmacy mail order

india pharmacy mail order world pharmacy india and reputable indian online pharmacy indian pharmacy online

best india pharmacy: indian pharmacy – top 10 pharmacies in india

indian pharmacy: indian pharmacy online – Medicine From India

RxExpressMexico mexican online pharmacy mexican rx online

http://medicinefromindia.com/# Medicine From India

indian pharmacy top 10 online pharmacy in india or best online pharmacy india

https://images.google.dk/url?sa=t&url=https://medicinefromindia.com online pharmacy india

best india pharmacy india online pharmacy and top 10 online pharmacy in india top 10 pharmacies in india

indian pharmacy: indian pharmacy online – indian pharmacy online shopping

RxExpressMexico: Rx Express Mexico – mexico drug stores pharmacies

cheap canadian pharmacy is canadian pharmacy legit or real canadian pharmacy

http://davidpawson.org/resources/resource/416?return_url=http://expressrxcanada.com/ the canadian drugstore

reputable canadian pharmacy canadian discount pharmacy and canadian pharmacy 365 best canadian online pharmacy

http://medicinefromindia.com/# best online pharmacy india

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa or buying prescription drugs in mexico online

http://clients1.google.cat/url?sa=i&url=https://rxexpressmexico.com pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

mexican rx online mexico pharmacies prescription drugs and mexican rx online buying prescription drugs in mexico

indian pharmacy online shopping: indian pharmacy online shopping – reputable indian pharmacies

canadian pharmacy reviews Express Rx Canada canadian drugs online

indian pharmacy: MedicineFromIndia – indian pharmacy online shopping

india pharmacy buy medicines online in india or indian pharmacies safe

https://maps.google.com.pa/url?sa=i&url=https://medicinefromindia.com india pharmacy

indian pharmacy reputable indian online pharmacy and buy medicines online in india indian pharmacy paypal

https://medicinefromindia.shop/# MedicineFromIndia

pharmacy website india Online medicine home delivery or online shopping pharmacy india

https://images.google.com.ph/url?q=https://medicinefromindia.com world pharmacy india

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india Online medicine home delivery and online shopping pharmacy india cheapest online pharmacy india

medicine courier from India to USA Medicine From India medicine courier from India to USA

indian pharmacy online: indian pharmacy online – indian pharmacy

http://pinupaz.top/# pinup az

пин ап казино официальный сайт: пин ап казино официальный сайт – пин ап казино официальный сайт

pin-up pin-up casino giris pinup az

http://pinuprus.pro/# пин ап казино

pin up вход пин ап зеркало пинап казино

http://pinuprus.pro/# пин ап казино

пин ап вход: пин ап зеркало – pin up вход

вавада официальный сайт вавада вавада зеркало

https://vavadavhod.tech/# vavada

pin-up: pin-up casino giris – pin up

пинап казино пинап казино pin up вход

http://pinuprus.pro/# пин ап зеркало

pin-up: pin-up – pin-up casino giris

пин ап казино официальный сайт пин ап вход or пинап казино

https://www.google.com.jm/url?sa=t&url=https://pinuprus.pro пинап казино

пин ап зеркало пин ап казино and пин ап казино пин ап казино официальный сайт

pin-up casino giris: pin-up – pin up az

вавада vavada casino вавада зеркало

http://vavadavhod.tech/# вавада зеркало

пин ап вход: pin up вход – пин ап зеркало

pin up pinup az or pin up

https://www.google.fi/url?q=https://pinupaz.top pin-up

pin up az pin-up casino giris and pin-up pin up az

пин ап казино: пин ап вход – пинап казино

вавада вавада казино вавада официальный сайт

пинап казино pin up вход or пинап казино

http://tanganrss.com/rsstxt/cushion.php?url=pinuprus.pro пин ап казино официальный сайт

пинап казино пин ап казино and пинап казино пинап казино

pin-up: pin up az – pin-up casino giris

vavada: вавада официальный сайт – vavada

vavada casino: vavada вход – vavada вход

pin up az pin up or pin-up casino giris

https://images.google.com.br/url?sa=t&url=http://pinupaz.top pin up casino

pin-up pin up azerbaycan and pin up pin up

vavada: vavada – вавада зеркало

пинап казино: пин ап казино – пинап казино

вавада казино vavada вход or vavada

https://toolbarqueries.google.ge/url?q=http://vavadavhod.tech вавада казино

vavada вавада and vavada casino вавада

http://vavadavhod.tech/# вавада

pin-up: pin-up casino giris – pin up azerbaycan

pin up casino pin-up pin up

pin up вход pin up вход or пин ап вход

https://www.google.nu/url?sa=t&url=https://pinuprus.pro пин ап зеркало

пинап казино пин ап казино and pin up вход пин ап зеркало

пин ап казино официальный сайт: pin up вход – pin up вход

пин ап зеркало пин ап казино официальный сайт or пин ап зеркало

https://cse.google.com.tj/url?q=https://pinuprus.pro пин ап казино официальный сайт

пинап казино пин ап казино официальный сайт and pin up вход пинап казино

http://vavadavhod.tech/# vavada casino

пин ап казино: пин ап казино – pin up вход

пин ап вход пин ап казино пинап казино

pin up casino: pin up az – pin up

http://pinuprus.pro/# пинап казино

вавада казино вавада or вавада официальный сайт

http://www.google.st/url?q=https://vavadavhod.tech вавада

вавада вавада зеркало and vavada vavada casino

пинап казино: пин ап зеркало – пинап казино

pin-up pinup az pin up casino

пин ап зеркало: pin up вход – pin up вход

pin up azerbaycan: pin up casino – pinup az

пин ап вход пин ап казино or pin up вход

http://ca.croftprimary.co.uk/warrington/primary/croft/arenas/schoolwebsite/calendar/CookiePolicy.action?backto=http://pinuprus.pro пин ап казино официальный сайт

pin up вход пин ап казино официальный сайт and пин ап зеркало пин ап казино

http://pinupaz.top/# pin up azerbaycan

пин ап казино: пин ап зеркало – пин ап вход

pin up azerbaycan pin up casino or pin-up

https://maps.google.com.gi/url?sa=t&url=https://pinupaz.top pinup az

pin up casino pin-up casino giris and pin up az pin-up

пин ап казино пин ап зеркало пинап казино

http://pinuprus.pro/# пинап казино

pin up вход: pin up вход – пин ап казино официальный сайт

vavada vavada вход or vavada

http://images.google.bi/url?q=https://vavadavhod.tech вавада официальный сайт

vavada вавада and вавада вавада

вавада казино: вавада зеркало – вавада казино

vavada vavada вход вавада официальный сайт

пин ап вход пин ап зеркало or пинап казино

https://cse.google.co.ke/url?q=https://pinuprus.pro пин ап вход

пин ап зеркало пин ап казино официальный сайт and pin up вход пин ап казино официальный сайт

https://pinuprus.pro/# pin up вход

пин ап казино официальный сайт pin up вход or пин ап зеркало

https://www.google.com.eg/url?q=https://pinuprus.pro pin up вход

пинап казино пинап казино and пин ап казино официальный сайт пинап казино

pin up azerbaycan: pinup az – pin-up casino giris

pin up azerbaycan pin up casino pin up azerbaycan

https://pinupaz.top/# pin up az

pin up вход: пин ап казино – пин ап казино

https://pinuprus.pro/# пин ап казино

vavada casino vavada casino vavada

pin up casino: pin-up casino giris – pin up casino

пин ап зеркало: пинап казино – pin up вход

пин ап зеркало пин ап вход or пин ап казино официальный сайт

https://www.k-to.ru/bitrix/rk.php?goto=http://pinuprus.pro pin up вход

пин ап вход пинап казино and pin up вход pin up вход

пин ап казино официальный сайт пин ап казино or пинап казино

https://maps.google.cz/url?sa=t&url=https://pinuprus.pro пин ап зеркало

pin up вход пин ап зеркало and пинап казино пин ап казино официальный сайт

pin-up casino giris pin-up casino giris or pin up az

https://images.google.tg/url?sa=t&url=https://pinupaz.top pinup az

pin up casino pin up casino and pinup az pin-up casino giris

https://vavadavhod.tech/# vavada вход

пин ап казино официальный сайт: пинап казино – pin up вход

pinup az pin up casino pinup az

вавада официальный сайт вавада or вавада

http://www.security-scanner-firing-range.com/reflected/url/href?q=https://vavadavhod.tech vavada casino

вавада казино vavada and vavada вавада казино

https://pinuprus.pro/# пин ап зеркало

вавада: вавада официальный сайт – vavada вход

пин ап вход пин ап казино официальный сайт or пин ап вход

http://www.kip-k.ru/best/sql.php?=pinuprus.pro пин ап казино

pin up вход pin up вход and пин ап вход пин ап вход

пин ап зеркало pin up вход or пин ап казино

http://pachl.de/url?q=https://pinuprus.pro:: пин ап казино

пин ап казино официальный сайт пин ап вход and пин ап зеркало пин ап зеркало

pin up azerbaycan pin-up or pin up azerbaycan

https://maps.google.is/url?sa=t&url=https://pinupaz.top pin up

pin up pin up azerbaycan and pin-up pin-up

http://vavadavhod.tech/# вавада казино

вавада официальный сайт: vavada casino – vavada вход

vavada casino: vavada – вавада зеркало

вавада vavada вход or вавада казино

https://www.google.me/url?q=https://vavadavhod.tech vavada casino

vavada vavada вход and vavada вавада казино

pinup az: pin up az – pin up casino

https://vavadavhod.tech/# vavada вход

пин ап казино официальный сайт pin up вход пинап казино

pinup az pin up az or pinup az

https://kaketosdelano.ml/proxy.php?link=https://pinupaz.top pin up casino

pin-up pin-up and pin up az pin-up casino giris

пин ап вход пин ап зеркало or пин ап зеркало

http://maps.google.je/url?q=http://pinuprus.pro pin up вход

пин ап казино официальный сайт пин ап зеркало and пин ап казино пинап казино

пин ап казино официальный сайт пинап казино or пин ап вход

http://www.fmisrael.com/Error.aspx?url=http://pinuprus.pro пин ап зеркало

пин ап казино pin up вход and пин ап зеркало пин ап казино

вавада: вавада – vavada casino

http://pinuprus.pro/# pin up вход

pinup az pin up casino pin up az

pin up вход: pin up вход – pin up вход

https://pinupaz.top/# pin-up

vavada вход вавада or vavada

https://maps.google.vu/url?q=https://vavadavhod.tech вавада

вавада зеркало vavada вход and вавада казино вавада казино

пин ап вход пин ап вход пин ап казино официальный сайт

pin-up casino giris pin-up or pin up az

http://ixawiki.com/link.php?url=http://pinupaz.top pin up

pinup az pin up and pin up azerbaycan pin up casino

пин ап казино: пин ап вход – пин ап вход

вавада казино: vavada casino – vavada

pin up вход пин ап зеркало or пин ап казино

https://top.hange.jp/linkdispatch/dispatch?targetUrl=http://pinuprus.pro пин ап казино официальный сайт

пин ап вход пин ап зеркало and pin up вход пинап казино

пинап казино пин ап казино or pin up вход

https://www.google.rs/url?q=https://pinuprus.pro пин ап вход

пин ап вход пин ап казино and пин ап казино пин ап вход

vavada casino: вавада казино – вавада зеркало

pinup az: pin-up – pin up casino

https://pinuprus.pro/# пин ап вход

vavada вход vavada вход or вавада зеркало

http://images.google.ee/url?q=https://vavadavhod.tech вавада казино

вавада vavada casino and вавада официальный сайт вавада

pin up casino: pin-up – pin up

вавада зеркало вавада зеркало вавада

пин ап казино официальный сайт пин ап казино or пин ап вход

https://maps.google.co.ug/url?rct=t&sa=t&url=https://pinuprus.pro pin up вход

pin up вход пинап казино and пин ап казино официальный сайт pin up вход

пин ап вход пин ап зеркало or пинап казино

http://www.linkestan.com/frame-click.asp?url=http://pinuprus.pro/ пин ап зеркало

пин ап вход pin up вход and пин ап казино пин ап казино официальный сайт

вавада: vavada вход – vavada casino

https://pinupaz.top/# pin up azerbaycan

вавада казино вавада казино or vavada casino

https://maps.google.ae/url?q=https://vavadavhod.tech вавада казино

vavada casino vavada casino and vavada вход вавада казино

pin up вход: пин ап вход – пинап казино

https://pinupaz.top/# pin up azerbaycan

vavada вход вавада зеркало вавада казино

pin up az: pin up casino – pin up az

пин ап зеркало пин ап казино официальный сайт or пин ап зеркало

http://cdiabetes.com/redirects/offer.php?URL=https://pinuprus.pro пин ап зеркало

пинап казино пин ап зеркало and pin up вход пин ап казино

вавада официальный сайт: вавада – вавада казино

пин ап казино официальный сайт pin up вход or пин ап казино

http://socialleadwizard.net/bonus/index.php?aff=http://pinuprus.pro/ пин ап вход

pin up вход пинап казино and пин ап казино официальный сайт пинап казино

http://pinuprus.pro/# пин ап вход

пин ап зеркало пин ап казино пинап казино

pinup az: pin up az – pinup az

vavada casino: vavada casino – вавада

vavada вход vavada or vavada

https://www.nbmain.com/nbAvailability.jsp?innkey=mcdaniel&backpage=https://vavadavhod.tech/ вавада официальный сайт

vavada casino vavada and вавада казино vavada

https://pinupaz.top/# pin up azerbaycan

pinup az pin up azerbaycan pin-up

vavada casino: вавада – вавада официальный сайт

pin up вход пин ап казино официальный сайт or pin up вход

https://toolbarqueries.google.gp/url?q=https://pinuprus.pro пин ап зеркало

пинап казино пин ап казино and пинап казино пинап казино

пинап казино пин ап вход or пин ап зеркало

https://www.google.com.pr/url?q=https://pinuprus.pro пин ап казино

пинап казино пин ап казино and пин ап казино официальный сайт пин ап казино

пинап казино пинап казино пинап казино

vavada casino: вавада казино – vavada вход

https://vavadavhod.tech/# вавада зеркало

вавада официальный сайт: вавада казино – vavada casino

https://pinuprus.pro/# пин ап казино официальный сайт

пин ап казино официальный сайт пин ап вход or пин ап казино официальный сайт

https://www.ficpa.org/content/membernet/secure/choose/dues-reminder.aspx?returnurl=http://pinuprus.pro пин ап зеркало

пин ап казино пин ап зеркало and пинап казино пин ап вход

pin up вход пин ап вход or пин ап зеркало

https://www.lepetitcornillon.fr/externe.php?site=http://pinuprus.pro pin up вход

пинап казино пин ап казино and пин ап зеркало пин ап вход

пин ап казино пин ап вход пинап казино

pin up azerbaycan: pin up azerbaycan – pin-up

http://vavadavhod.tech/# vavada casino

вавада официальный сайт vavada casino or вавада официальный сайт

http://phpooey.com/?URL=vavadavhod.tech vavada casino

vavada вход вавада казино and vavada вход вавада

пин ап казино официальный сайт: пинап казино – pin up вход

pin up casino pin up casino pinup az

https://vavadavhod.tech/# vavada casino

пинап казино пинап казино or pin up вход

http://andreasgraef.de/url?q=https://pinuprus.pro:: пин ап казино

пинап казино пин ап казино официальный сайт and pin up вход пин ап казино

pinup az: pin up az – pin-up casino giris

пинап казино пин ап зеркало пин ап казино официальный сайт

пин ап зеркало пин ап казино официальный сайт or пинап казино

https://images.google.com.vc/url?q=https://pinuprus.pro пин ап казино официальный сайт

пинап казино пинап казино and пин ап казино официальный сайт пин ап зеркало

https://vavadavhod.tech/# vavada casino

вавада официальный сайт vavada casino or вавада

https://www.google.com.sa/url?q=https://vavadavhod.tech вавада зеркало

vavada вавада официальный сайт and вавада казино вавада

вавада казино: вавада – вавада казино

пин ап вход: pin up вход – пинап казино

pin-up pinup az pin-up casino giris

http://pinupaz.top/# pin up az

http://vavadavhod.tech/# вавада официальный сайт

пинап казино пин ап зеркало пинап казино

пин ап казино pin up вход or пин ап вход

https://www.google.co.id/url?sa=t&url=https://pinuprus.pro пин ап вход

пин ап казино пин ап зеркало and пин ап казино официальный сайт пин ап казино

пинап казино пин ап вход or pin up вход

http://images.google.co.ma/url?q=http://pinuprus.pro пинап казино

пин ап казино пин ап казино официальный сайт and пинап казино пин ап зеркало

pin-up casino giris: pin-up casino giris – pinup az

http://vavadavhod.tech/# vavada casino

пин ап вход pin up вход pin up вход

https://vavadavhod.tech/# vavada

пин ап зеркало: пин ап вход – пин ап казино

vavada casino vavada вход vavada

пин ап вход пин ап казино официальный сайт or пинап казино

https://image.google.co.bw/url?q=https://pinuprus.pro пинап казино

pin up вход pin up вход and пин ап вход пин ап казино

pin up вход пин ап казино официальный сайт or pin up вход

http://www.codetools.ir/tools/static-image/4.php?l=http://pinuprus.pro пин ап зеркало

пинап казино пин ап казино официальный сайт and пин ап казино официальный сайт пинап казино

пин ап зеркало: пинап казино – пин ап казино официальный сайт

http://vavadavhod.tech/# вавада зеркало

pin up вход: pin up вход – пин ап вход

вавада казино vavada casino vavada вход

pin-up casino giris: pin up casino – pin-up casino giris

https://pinuprus.pro/# пин ап зеркало

safe online pharmacy no doctor visit required cheap Viagra online

FDA approved generic Cialis: secure checkout ED drugs – generic tadalafil

https://maxviagramd.shop/# generic sildenafil 100mg

cheap Cialis online generic tadalafil FDA approved generic Cialis

https://maxviagramd.shop/# same-day Viagra shipping

legal Modafinil purchase: doctor-reviewed advice – modafinil legality

reliable online pharmacy Cialis buy generic Cialis online online Cialis pharmacy

buy modafinil online: safe modafinil purchase – doctor-reviewed advice

https://modafinilmd.store/# purchase Modafinil without prescription

FDA approved generic Cialis online Cialis pharmacy or cheap Cialis online

http://www.codetools.ir/tools/static-image/4.php?l=http://zipgenericmd.com reliable online pharmacy Cialis

discreet shipping ED pills cheap Cialis online and best price Cialis tablets best price Cialis tablets

fast Viagra delivery: no doctor visit required – discreet shipping

modafinil legality safe modafinil purchase or Modafinil for sale

http://maps.google.mv/url?q=https://modafinilmd.store safe modafinil purchase

modafinil pharmacy legal Modafinil purchase and legal Modafinil purchase modafinil 2025

trusted Viagra suppliers best price for Viagra or no doctor visit required

http://vmus.adu.org.za/vm_search.php?database=vimma&prj_acronym=MammalMAP&db=vimma&URL=http://maxviagramd.shop&Logo=images/vimma_logo.png&Headline=Virtual trusted Viagra suppliers

safe online pharmacy discreet shipping and no doctor visit required generic sildenafil 100mg

online Cialis pharmacy online Cialis pharmacy best price Cialis tablets

doctor-reviewed advice: legal Modafinil purchase – modafinil 2025

affordable ED medication: FDA approved generic Cialis – discreet shipping ED pills

modafinil pharmacy: doctor-reviewed advice – buy modafinil online

discreet shipping: Viagra without prescription – fast Viagra delivery

http://zipgenericmd.com/# online Cialis pharmacy

verified Modafinil vendors doctor-reviewed advice or legal Modafinil purchase

https://cse.google.mv/url?q=https://modafinilmd.store legal Modafinil purchase

purchase Modafinil without prescription Modafinil for sale and buy modafinil online buy modafinil online

generic sildenafil 100mg same-day Viagra shipping or order Viagra discreetly

https://toolbarqueries.google.ac/url?q=https://maxviagramd.shop secure checkout Viagra

safe online pharmacy trusted Viagra suppliers and cheap Viagra online fast Viagra delivery

legal Modafinil purchase verified Modafinil vendors modafinil 2025

generic sildenafil 100mg: legit Viagra online – safe online pharmacy

FDA approved generic Cialis: order Cialis online no prescription – Cialis without prescription

safe modafinil purchase buy modafinil online doctor-reviewed advice

FDA approved generic Cialis secure checkout ED drugs or FDA approved generic Cialis

http://www.cookinggamesclub.com/partner/zipgenericmd.com/ online Cialis pharmacy

order Cialis online no prescription discreet shipping ED pills and reliable online pharmacy Cialis reliable online pharmacy Cialis

modafinil legality: modafinil 2025 – buy modafinil online

doctor-reviewed advice: buy modafinil online – modafinil 2025

https://maxviagramd.com/# trusted Viagra suppliers

legal Modafinil purchase verified Modafinil vendors or legal Modafinil purchase

https://www.google.com.fj/url?sa=t&url=https://modafinilmd.store safe modafinil purchase

safe modafinil purchase modafinil 2025 and legal Modafinil purchase legal Modafinil purchase

fast Viagra delivery: same-day Viagra shipping – Viagra without prescription

generic sildenafil 100mg: Viagra without prescription – fast Viagra delivery

http://modafinilmd.store/# purchase Modafinil without prescription

verified Modafinil vendors: modafinil legality – safe modafinil purchase

legit Viagra online: fast Viagra delivery – legit Viagra online

best price Cialis tablets reliable online pharmacy Cialis or best price Cialis tablets

https://maps.google.com.cu/url?rct=j&sa=t&url=https://zipgenericmd.com affordable ED medication

reliable online pharmacy Cialis Cialis without prescription and best price Cialis tablets affordable ED medication

no doctor visit required same-day Viagra shipping generic sildenafil 100mg

generic sildenafil 100mg: secure checkout Viagra – best price for Viagra

affordable ED medication FDA approved generic Cialis or cheap Cialis online

https://images.google.ms/url?sa=t&url=https://zipgenericmd.com buy generic Cialis online

affordable ED medication cheap Cialis online and cheap Cialis online reliable online pharmacy Cialis

https://modafinilmd.store/# modafinil 2025

legal Modafinil purchase: modafinil legality – Modafinil for sale

affordable ED medication discreet shipping ED pills generic tadalafil

safe modafinil purchase: modafinil legality – doctor-reviewed advice

discreet shipping fast Viagra delivery or cheap Viagra online

https://clients1.google.com.ua/url?sa=t&url=https://maxviagramd.shop trusted Viagra suppliers

legit Viagra online Viagra without prescription and same-day Viagra shipping Viagra without prescription

http://modafinilmd.store/# buy modafinil online

legal Modafinil purchase: buy modafinil online – legal Modafinil purchase

secure checkout ED drugs buy generic Cialis online or cheap Cialis online

https://www.google.com.ph/url?q=https://zipgenericmd.com secure checkout ED drugs

Cialis without prescription Cialis without prescription and affordable ED medication affordable ED medication

modafinil legality verified Modafinil vendors Modafinil for sale

https://maxviagramd.com/# legit Viagra online

best price Cialis tablets: online Cialis pharmacy – FDA approved generic Cialis

online Cialis pharmacy online Cialis pharmacy or best price Cialis tablets

https://www.google.am/url?q=https://zipgenericmd.com generic tadalafil

order Cialis online no prescription secure checkout ED drugs and FDA approved generic Cialis reliable online pharmacy Cialis

Cialis without prescription: generic tadalafil – discreet shipping ED pills

verified Modafinil vendors doctor-reviewed advice or modafinil 2025

https://cse.google.mu/url?sa=t&url=https://modafinilmd.store modafinil pharmacy

safe modafinil purchase modafinil 2025 and doctor-reviewed advice modafinil 2025

http://prednihealth.com/# PredniHealth

how to get cheap clomid without a prescription: get clomid – can i buy clomid

how to buy cheap clomid tablets: where can i get cheap clomid – can i purchase generic clomid online

rexall pharmacy amoxicillin 500mg medicine amoxicillin 500mg Amo Health Care

https://clomhealth.com/# where to buy generic clomid pill

can i order clomid for sale: how to buy cheap clomid price – cost clomid without rx

azithromycin amoxicillin: amoxicillin 50 mg tablets – purchase amoxicillin online

amoxicillin 875 125 mg tab Amo Health Care Amo Health Care

https://clomhealth.shop/# where to buy generic clomid without insurance

generic amoxicillin cost: buy amoxil – amoxicillin brand name

buying clomid without prescription: generic clomid no prescription – can i buy clomid for sale

http://clomhealth.com/# cost of generic clomid pill

can i get clomid without rx: order generic clomid without insurance – where to buy clomid without insurance

PredniHealth PredniHealth PredniHealth

cost of generic clomid no prescription: how to get cheap clomid – cheap clomid now

buy amoxicillin 500mg capsules uk amoxicillin 250 mg or price of amoxicillin without insurance

http://www.toponweb.net/vm.asp?url=https://amohealthcare.store amoxicillin 500mg capsules antibiotic

order amoxicillin online amoxicillin online canada and amoxicillin 500 mg brand name 875 mg amoxicillin cost

prednisone otc uk prednisone without prescription or buy 40 mg prednisone

https://cse.google.ms/url?sa=t&url=https://prednihealth.com india buy prednisone online

prednisone 25mg from canada buying prednisone from canada and prednisone 5443 can i purchase prednisone without a prescription

https://clomhealth.com/# can i get clomid pill

Amo Health Care: amoxicillin 500mg without prescription – Amo Health Care

buy amoxicillin from canada Amo Health Care amoxicillin pharmacy price

cost cheap clomid: can i get cheap clomid tablets – how can i get cheap clomid online

prednisone 20mg price order prednisone 10 mg tablet or prednisone buy canada

https://www.google.je/url?q=https://prednihealth.shop prednisone 5 tablets

over the counter prednisone cream price of prednisone 5mg and where can i buy prednisone without a prescription prednisone over the counter

https://clomhealth.com/# cost cheap clomid now

Amo Health Care: amoxicillin 500mg price in canada – amoxicillin 500mg price in canada

PredniHealth: prednisone tabs 20 mg – prednisone 20 mg tablet

can you get clomid how to get cheap clomid for sale how can i get clomid without insurance

can you buy cheap clomid without insurance order cheap clomid or how to buy clomid without rx

https://cse.google.mu/url?sa=t&url=https://clomhealth.com how to buy generic clomid online

cheap clomid online cost of cheap clomid pills and cost cheap clomid online get cheap clomid without rx

cost of amoxicillin amoxicillin 500 mg or <a href=" http://www.e-anim.com/test/E_GuestBook.asp?a=buy+teva+generic+viagra “>amoxicillin 500mg capsule buy online

https://toolbarqueries.google.com.sb/url?q=https://amohealthcare.store ampicillin amoxicillin

can we buy amoxcillin 500mg on ebay without prescription buy cheap amoxicillin online and azithromycin amoxicillin amoxicillin 250 mg price in india

https://prednihealth.shop/# prednisone 30 mg tablet

Amo Health Care: generic amoxicillin cost – amoxicillin 500 mg tablets

prednisone without prescription: PredniHealth – PredniHealth

generic amoxil 500 mg Amo Health Care amoxicillin online no prescription

https://clomhealth.com/# can you get generic clomid

can i buy cheap clomid price: Clom Health – can i order cheap clomid prices

can i purchase prednisone without a prescription prednisone 5mg price or prednisone 54

https://www.google.com.ec/url?q=https://prednihealth.shop prednisone buy canada

buy prednisone without a prescription best price prednisone 15 mg daily and prednisone 40 mg tablet how to purchase prednisone online

prednisone 25mg from canada: PredniHealth – where to get prednisone

Amo Health Care cost of amoxicillin 875 mg amoxicillin script

how to get generic clomid price can i order cheap clomid pill or can you get cheap clomid without a prescription

https://clients1.google.com.vc/url?q=https://clomhealth.com buying clomid without dr prescription

order generic clomid no prescription where to get generic clomid and how to get generic clomid online how to buy clomid without dr prescription

cialis erection: cialis super active plus reviews – truth behind generic cialis

https://tadalaccess.com/# cheap cialis 5mg

generic cialis from india TadalAccess cialis tadalafil 5mg once a day

buy cheap tadalafil online: TadalAccess – recreational cialis

free cialis samples: canadian cialis – stockists of cialis

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis online no prescription australia

buy cialis without a prescription: Tadal Access – best time to take cialis 20mg

cialis instructions buying cialis online canadian order what is the active ingredient in cialis

cialis tablets for sell: Tadal Access – best time to take cialis

https://tadalaccess.com/# tadalafil cialis

cialis with dapoxetine: Tadal Access – buy cialis generic online

cialis 10mg price cialis free trial how long does tadalafil take to work

https://tadalaccess.com/# tadalafil dose for erectile dysfunction

cialis shipped from usa: Tadal Access – over the counter cialis walgreens

cialis advertisement cialis coupon walmart or where to get the best price on cialis

https://www.google.gm/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com sunrise pharmaceutical tadalafil

difference between tadalafil and sildenafil cialis covered by insurance and what is the cost of cialis cialis super active vs regular cialis

cialis no prescription overnight delivery Tadal Access cialis black 800 mg pill house

cialis tadalafil 20mg kaufen: cialis for prostate – buy generic cialis online

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis side effects a wife’s perspective

cialis 80 mg dosage: Tadal Access – what possible side effect should a patient taking tadalafil report to a physician quizlet

what to do when cialis stops working adcirca tadalafil cialis for daily use side effects

buy generic cialiss: cialis amazon – evolution peptides tadalafil

https://tadalaccess.com/# vigra vs cialis

cialis price walmart cheap generic cialis canada or purchase brand cialis

http://www.kfiz.com/Redirect.aspx?destination=http://tadalaccess.com/ generic cialis tadalafil 20 mg from india

tadalafil (tadalis-ajanta) how long before sex should i take cialis and where to get generic cialis without prescription buy tadalafil cheap online

tadalafil tablets 20 mg global: TadalAccess – tadalafil cheapest online

pharmacy 365 cialis cialis dosage 40 mg or cialis tadalafil 5mg once a day

http://aanorthflorida.org/es/redirect.asp?url=http://tadalaccess.com cialis daily vs regular cialis

online cialis no prescription tadalafil generic in usa and buy cialis online safely cialis online reviews

cialis otc switch when is the best time to take cialis or where can i buy cialis

http://goldankauf-engelskirchen.de/out.php?link=https://tadalaccess.com cialis for prostate

poppers and cialis where to get generic cialis without prescription and mint pharmaceuticals tadalafil reviews what happens when you mix cialis with grapefruit?

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis side effects

stockists of cialis cialis without a doctor prescription canada tadalafil generic usa

cialis brand no prescription 365: buy tadalafil online paypal – cialis canada free sample

cialis sample request form: cialis and cocaine – cialis amazon

generic tadalafil canada: cialis online canada ripoff – when will generic cialis be available

cialis free sample TadalAccess cialis prescription cost

cialis 20 mg best price: can i take two 5mg cialis at once – canadian pharmacy cialis

canadian no prescription pharmacy cialis cialis w/o perscription or stendra vs cialis

https://cse.google.com.bo/url?sa=t&url=https://tadalaccess.com tadalafil generico farmacias del ahorro

maxim peptide tadalafil citrate cialis dopoxetine and cialis generic cvs cialis manufacturer coupon lilly

buy cialis united states canada pharmacy cialis or cialis generic online

https://www.google.com.gi/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com cialis without a doctor prescription canada

cialis available in walgreens over counter?? purchase cialis and dapoxetine and tadalafil cialis prostate

https://tadalaccess.com/# what is cialis used for

where to buy cialis in canada: where to buy liquid cialis – generic cialis 20 mg from india

buy cialis cheap fast delivery how much is cialis without insurance or pharmacy 365 cialis

https://images.google.com.ar/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com cialis drug class

buying generic cialis cialis tadalafil tablets and tadalafil no prescription forum cialis best price

generic cialis: Tadal Access – what are the side effects of cialis

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis and melanoma

cialis canada over the counter: cialis walmart – best reviewed tadalafil site

cialis 20mg review cialis bestellen deutschland cialis slogan

cheap tadalafil no prescription: tadalafil versus cialis – tadalafil softsules tuf 20

cialis price costco buy cialis online usa or adcirca tadalafil

http://lonevelde.lovasok.hu/out_link.php?url=https://tadalaccess.com u.s. pharmacy prices for cialis

tadalafil 40 mg india cialis tablets and why does tadalafil say do not cut pile when to take cialis 20mg

https://tadalaccess.com/# buy tadalafil online no prescription

cialis bodybuilding: does cialis make you last longer in bed – what is the generic name for cialis

cialis how long does it last: cialis alcohol – price comparison tadalafil

how well does cialis work TadalAccess buy liquid tadalafil online

how long does cialis take to work 10mg cheaper alternative to cialis or cialis male enhancement

https://maps.google.mn/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com cialis on sale

no prescription cialis cialis black in australia and generic cialis vs brand cialis reviews cialis online no prior prescription

https://tadalaccess.com/# what to do when cialis stops working

cialis black 800 to buy in the uk one pill: how much does cialis cost per pill – shop for cialis

tadalafil troche reviews: generic tadalafil in us – cialis review

how long does cialis last 20 mg TadalAccess cialis what is it

https://tadalaccess.com/# how long does it take cialis to start working

cialis pills pictures typical cialis prescription strength or cialis cost at cvs

https://toolbarqueries.google.co.il/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com canadian pharmacy cialis brand

cialis same as tadalafil cialis tablets for sell and when will cialis be over the counter cialis 20mg side effects

best research tadalafil 2017 centurion laboratories tadalafil review or cialis company

https://maps.google.nu/url?sa=t&url=https://tadalaccess.com price of cialis at walmart

cialis australia online shopping buy liquid cialis online and walgreens cialis prices cialis prescription online

cialis for sale online in canada: Tadal Access – erectile dysfunction tadalafil

where to buy cialis soft tabs: TadalAccess – how long does it take for cialis to take effect

what is the difference between cialis and tadalafil? cialis 20mg side effects cialis indications

pictures of cialis pills cialis dopoxetine or reliable source cialis

https://clients1.google.lu/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com cialis how long

canada drug cialis cialis when to take and cialis generic timeline cialis definition

https://tadalaccess.com/# tadalafil vidalista

where to buy cialis cheap: TadalAccess – cialis for sale

buy cialis shipment to russia: TadalAccess – what is the use of tadalafil tablets

achats produit tadalafil pour femme en ligne tadalafil long term usage cheapest cialis 20 mg

https://tadalaccess.com/# tadalafil and sildenafil taken together

cialis is for daily use: over the counter cialis – cialis discount coupons

does cialis lower your blood pressure does cialis shrink the prostate or cialis generic cost

https://www.google.co.ma/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com cialis information

tadalafil canada is it safe cialis street price and buy cialis united states cialis 50mg

cialis not working anymore generic cialis super active tadalafil 20mg or is cialis covered by insurance

https://images.google.com.vc/url?sa=t&url=https://tadalaccess.com where to get free samples of cialis

best price on generic cialis cialis no perscrtion and cialis tadalafil cialis on sale

cialis online overnight shipping: TadalAccess – buy cheap cialis online with mastercard

trusted online store to buy cialis cialis commercial bathtub how long does cialis stay in your system

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis generic best price that accepts mastercard

cialis tadalafil tablets cialis before and after or cialis where to buy in las vegas nv

https://toolbarqueries.google.pl/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com paypal cialis no prescription

generic cialis available in canada tadalafil tablets 20 mg reviews and what is the generic name for cialis cialis insurance coverage

cialis blood pressure: Tadal Access – cialis pills for sale

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis online without pres

purchase cialis online cialis stopped working cialis cheapest price

cialis 5mg daily: side effects of cialis daily – super cialis

cialis max dose: cialis commercial bathtub – cialis daily review

buy liquid cialis online cialis over the counter usa or generic cialis super active tadalafil 20mg

https://toolbarqueries.google.ms/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com tadalafil citrate liquid

buy cialis canada paypal average dose of tadalafil and cialis 5 mg tablet tadalafil lowest price

is tadalafil and cialis the same thing? cialis canada sale or buy cialis on line

http://sat.kuz.ru/engine/redirect.php?url=http://tadalaccess.com cialis coupon walmart

side effects of cialis cialis 80 mg dosage and special sales on cialis cialis canadian purchase

https://tadalaccess.com/# is tadalafil available in generic form

cialis 800 black canada TadalAccess what is the generic for cialis

how much is cialis without insurance: cialis what is it – cialis 5 mg tablet

what is cialis taken for: cialis price walgreens – free samples of cialis

cialis tadalafil 10 mg canadian pharmacy cialis or us pharmacy prices for cialis

https://www.google.com.bn/url?sa=t&url=https://tadalaccess.com cialis tadalafil

order cialis soft tabs cialis overnight deleivery and how many 5mg cialis can i take at once cialis over the counter at walmart

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis priligy online australia

cialis tadalafil cheapest online: Tadal Access – cialis overnight deleivery

cialis manufacturer coupon: cialis with out a prescription – cialis payment with paypal

https://tadalaccess.com/# tadalafil buy online canada

buy cialis with american express can tadalafil cure erectile dysfunction or over the counter cialis walgreens

http://www.thenailshop.ru/bitrix/rk.php?goto=http://tadalaccess.com/ prescription for cialis

cialis for bph reviews stendra vs cialis and mambo 36 tadalafil 20 mg cialis 2.5 mg

when will cialis be over the counter generic cialis 20 mg from india or tadalafil ingredients

http://prosports-shop.com/shop/display_cart?return_url=http://tadalaccess.com generic tadalafil cost

tadalafil and ambrisentan newjm 2015 tadalafil lowest price and when is the best time to take cialis cialis 5mg review

cheap cialis by post: TadalAccess – cialis and cocaine

what is the use of tadalafil tablets: Tadal Access – cialis how to use

cialis manufacturer coupon TadalAccess cialis manufacturer coupon

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis price walgreens

tadalafil generico farmacias del ahorro: TadalAccess – cialis logo

where to buy generic cialis ?: tadalafil generic cialis 20mg – cialis 20 mg how long does it take to work

cialis para que sirve cialis price per pill cialis soft

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis for daily use reviews

prices of cialis: cialis pills online – cialis over the counter at walmart

cialis com coupons: TadalAccess – cialis 5mg price walmart

printable cialis coupon buy cialis with american express or cialis coupon online

https://images.google.ki/url?sa=t&url=https://tadalaccess.com cialis 20mg tablets

cialis pricing cialis effects and tadalafil generic reviews п»їwhat can i take to enhance cialis

cialis online without a prescription Tadal Access where to buy cialis in canada

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis not working

cialis in canada: generic cialis online pharmacy – when is the best time to take cialis

tadalafil cost cvs: TadalAccess – paypal cialis no prescription

how long does cialis stay in your system Tadal Access cialis copay card

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis efectos secundarios

tadalafil tablets 20 mg reviews: TadalAccess – tadalafil professional review

buy cialis united states: para que sirve las tabletas cialis tadalafil de 5mg – cialis dosage side effects

cialis sample pack Tadal Access tadalafil oral jelly

generic cialis tadalafil 20mg india blue sky peptide tadalafil review or cialis and adderall

https://www.google.as/url?sa=t&url=https://tadalaccess.com canada cialis for sale

cialis generic best price overnight cialis delivery usa and find tadalafil tadalafil 10mg side effects

canadian online pharmacy cialis cialis manufacturer coupon or tadalafil professional review

http://anahit.fr/Home/Details/5d8dfabf-ef01-4804-aae4-4bbc8f8ebd3d?returnUrl=http://tadalaccess.com cialis price per pill

buy liquid cialis online cialis generico and teva generic cialis buy cialis online no prescription

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis slogan

cialis online without prescription: cialis 20 mg price walgreens – cialis 30 day free trial

tadalafil (exilar-sava healthcare) version of cialis] (rx) lowest price prices of cialis 20 mg or cialis free trial voucher

https://www.google.co.th/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com cialis 5mg review

cialis canada online canadian cialis no prescription and tadacip tadalafil natural alternative to cialis

cialis for performance anxiety: TadalAccess – cheap cialis free shipping

cheap cialis by post cialis by mail buy cialis tadalafil

https://tadalaccess.com/# how many mg of cialis should i take

tadalafil vidalista: how long does it take cialis to start working – best price on generic tadalafil

cialis payment with paypal: order cialis no prescription – when will generic cialis be available in the us

tadalafil review TadalAccess para que sirve las tabletas cialis tadalafil de 5mg

https://tadalaccess.com/# buy generic tadalafil online cheap

special sales on cialis cialis time or buy cialis without a prescription

https://www.google.co.id/url?sa=t&url=https://tadalaccess.com cialis logo

cialis in las vegas how many mg of cialis should i take and walgreens cialis prices when will generic cialis be available in the us

what is the active ingredient in cialis: generic cialis super active tadalafil 20mg – cialis and cocaine

best time to take cialis 5mg vidalista tadalafil reviews or sanofi cialis

http://www.reko-bioterra.de/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com overnight cialis delivery

cialis canada sale best price on cialis and san antonio cialis doctor cialis canada price

cialis 5mg how long does it take to work buy cialis online canada or free samples of cialis

http://easyfeed.info/easyfeed/feed2js.php?src=https://tadalaccess.com/ tadacip tadalafil

cialis las vegas tadalafil professional review and cialis 10mg price when will cialis be generic

cialis maximum dose: cialis coupon online – cialis definition

purchase cialis Tadal Access cialis tadalafil & dapoxetine

https://tadalaccess.com/# mambo 36 tadalafil 20 mg

cialis for sale online: TadalAccess – cialis super active reviews

how to take cialis: Tadal Access – how long does it take cialis to start working

buy cialis online in austalia: Tadal Access – cheapest 10mg cialis

https://tadalaccess.com/# buy cialis with american express

cialis 100mg TadalAccess buy cheapest cialis

cialis daily dosage tadalafil 40 mg india or order cialis canada

https://maps.google.pn/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com cialis online aust

cialis 10mg ireland cialis 5mg price cvs and cialis prices in mexico pregnancy category for tadalafil

cialis 800 black canada: para que sirve las tabletas cialis tadalafil de 5mg – cialis after prostate surgery

canadian pharmacy cialis 40 mg: TadalAccess – tadalafil price insurance

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis indien bezahlung mit paypal

cialis 20mg review Tadal Access poppers and cialis

cialis price costco: Tadal Access – is there a generic cialis available?

cialis canadian pharmacy: cialis generic cost – cialis medicare

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis 20 mg how long does it take to work

cialis free trial buy cialis canada cialis for sale toronto

cialis w/o perscription where can i get cialis or cialis not working first time

http://clients1.google.com.vn/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com cialis dapoxetine australia

cialis 50mg cheap tadalafil no prescription and canada drugs cialis cialis 10mg reviews

cialis dosis cialis shipped from usa or cialis lower blood pressure

https://www.google.com.ec/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com snorting cialis

how to take cialis cialis price south africa and oryginal cialis buy cialis without a prescription

cialis pill: TadalAccess – can tadalafil cure erectile dysfunction

where can i buy cialis over the counter: TadalAccess – buying cialis

https://tadalaccess.com/# canada cialis

does tadalafil lower blood pressure cialis super active real online store or cialis patent expiration

https://www.google.fi/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com cialis daily dosage

order cialis online is tadalafil as effective as cialis and cialis price costco cialis canadian purchase

pregnancy category for tadalafil TadalAccess cialis male enhancement

cheapest cialis online: buy cialis online reddit – cialis over the counter in spain

tadalafil vs cialis TadalAccess cialis 100mg review

https://tadalaccess.com/# tadalafil (exilar-sava healthcare) version of cialis] (rx) lowest price

mantra 10 tadalafil tablets taking cialis or what is tadalafil made from

http://www.tanadakenzai.co.jp/feed2js/feed2js.php?src=http://tadalaccess.com tadalafil ingredients

cialis manufacturer coupon cialis reviews and tadalafil 10mg side effects cialis sample request form

cialis overdose: when will generic cialis be available in the us – cialis online without a prescription

buy cheapest cialis: online cialis no prescription – cialis alternative over the counter

where to buy cialis soft tabs cialis when to take sildenafil vs cialis

buying cialis without prescription no prescription cialis or cialis for sale toronto

http://hanamura.shop/link.cgi?url=https://tadalaccess.com cheap cialis online overnight shipping

buy cialis generic online cialis when to take and cialis one a day where can i buy cialis

how long does it take cialis to start working how much tadalafil to take or purchase cialis online

http://elkashif.net/?URL=https://tadalaccess.com cialis canada pharmacy no prescription required

generic cialis super active tadalafil 20mg cialis before and after photos and difference between sildenafil and tadalafil where to buy cialis over the counter

https://tadalaccess.com/# generic cialis tadalafil 20mg reviews

when will generic cialis be available in the us: cialis super active plus reviews – cialis how to use

cialis 20 mg price walgreens Tadal Access can you drink wine or liquor if you took in tadalafil

cialis a domicilio new jersey: cialis sublingual – cialis 40 mg reviews

cialis 20 mg best price cialis pricing or cialis over the counter in spain

https://verify.authorize.net/anetseal/?pid=5a0e11fa-3743-4f5e-8789-a8edcbd83aef&rurl=http://tadalaccess.com cialis and high blood pressure

cialis online pharmacy australia buy tadalafil cheap and tadalafil tablets 20 mg global cialis black 800 mg pill house

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis from india online pharmacy

active ingredient in cialis TadalAccess cialis tadalafil 10 mg

mambo 36 tadalafil 20 mg: how much does cialis cost at walgreens – cialis coupon online

cheap t jet 60 cialis online buy cialis no prescription australia or prescription for cialis

https://cse.google.com.py/url?sa=t&url=https://tadalaccess.com stockists of cialis

difference between cialis and tadalafil tadalafil 5mg generic from us and peptide tadalafil reddit cialis for women

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis 100mg from china

cialis cheapest price cialis 20 mg from united kingdom or cialis online with no prescription

http://leefirstbaptistchurch.org/System/Login.asp?id=48747&Referer=http://tadalaccess.com great white peptides tadalafil

cialis side effects forum how long i have to wait to take tadalafil after antifugal and cialis 20 mg tablets and prices cheapest cialis online

teva generic cialis: TadalAccess – uses for cialis

cialis goodrx Tadal Access cialis price per pill

cialis 20mg side effects cialis sample or cialis dosage reddit

https://www.google.ms/url?sa=t&url=https://tadalaccess.com cialis 5mg how long does it take to work

vigra vs cialis cialis black in australia and most recommended online pharmacies cialis buy cialis from canada

viagara cialis levitra: Tadal Access – cialis for bph insurance coverage

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis and high blood pressure

buy voucher for cialis daily online TadalAccess cialis sample

buy cialis tadalafil purchase cialis online or cialis tadalafil 20mg tablets

https://www.google.ml/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com price of cialis at walmart

cialis generic best price cialis headache and cialis 20mg price buying cialis internet

tadalafil prescribing information: TadalAccess – buy tadalafil powder

cialis tablets Tadal Access cialis drug

https://tadalaccess.com/# cialis shipped from usa

cialis free what happens when you mix cialis with grapefruit? or tadalafil walgreens

http://variotecgmbh.de/url?q=https://tadalaccess.com cheapest cialis

what is cialis prescribed for free cialis samples and cialis tadalafil 20mg tablets tadalafil 20mg

cialis 100 mg usa walmart cialis price or generic cialis vs brand cialis reviews

https://artwinlive.com/widgets/1YhWyTF0hHoXyfkbLq5wpA0H?generated=true&color=dark&layout=list&showgigs=4&moreurl=https://tadalaccess.com canadian pharmacy online cialis

tadalafil prescribing information is tadalafil and cialis the same thing? and cialis over the counter at walmart cialis and nitrates

cialis lower blood pressure: Tadal Access – tadalafil dose for erectile dysfunction

online cialis prescription TadalAccess cialis used for

cialis how long best place to buy tadalafil online or cialis free

http://tyadnetwork.com/ads_top.php?url=https://tadalaccess.com/ cialis free trial 2018

cialis daily tadalafil buy online canada and cialis tadalafil tablets cialis generic cost

https://tadalaccess.com/# order cialis canada

what is cialis taken for: when will generic tadalafil be available – cialis dapoxetine europe

best price for cialis Tadal Access cialis for sale online in canada